Empire on holiday

It was artfully contrived by Augustus that in the

enjoyment of plenty the Romans should lose the memory of freedom.' When he

delivered himself of this judgement, Gibbon may have done an injustice to the

first emperor's aims, but as the historian of Empire he did not mistake the

consequence of his actions. Internal war was at an end; and not only Rome but

the whole Empire came to look to the Palatine as the source of all govern/ ment.

Thanks to what the Greeks had done, the Empire as a political unity was not so

much a collection of provinces as a vast network of cities whose status was that

of municipalities. The cities were the centres of education and culture; and to

a large extent they relieved the imperial government of the bur/ dens of

administration and assumed responsibility for security, communications and

tax/collection. As a way of life the Greek city triumphed; indeed, it was so

self/assured in its cultural heritage that practically speaking no Greek ever

heard the names of Horace or Virgil. But politically it had to stomach the loss

of the independence it had so long fought for; and there was perhaps a certain

wryness in the remark of the unctuous Aelius Aristides that 'of course, it is

more blessed to pay taxes to Rome than to receive tribute from others.'

Publius Aelius Aristides was the spokesman for the Greeks of his age. Born in

the Mysian backwoods where city life was introduced about the time of his birth

by the emperor Hadrian, he settled at Smyrna and with the help of a strong

constitution devoted himself to the care of his health. He nevertheless found

leisure for rhetorical exercises, and the address that he delivered to the

Romans about ad 143 strikes the keynote of the 'Golden Age': 'As though on

holiday,' he tells the Romans, 'the world has shed its burden of arms and

devotes itself freely to beautification

and festivity of every kind. The cities have relinquished their old feuds; and a

single rivalry possesses every one of them -to be the best and most beautiful of

all. Everywhere are gymnasia,

fountains, arches, temples, town halls and schools. The ailing world has been,

so to speak, scientifically restored to complete health. Donations flow

perpetually from you to the cities; and no one can tell who gets the largest

share because your bounty is so impartial. The cities positively gleam with

radiance and charm, and the whole earth is a pleasure garden. The smoke of

burning homes and warning beacons is gone with the wind from the face of land

and sea; instead we are confronted with spectacles of manifold charm and an

infinitude of public games. Thus, unquenchable like a sacred flame, the fair

never stops but passes on from place to place; and it is always continuing

somewhere, for the whole world has quahv fied for these blessings.'

They had never had it so good. 'There is no need of garrisons in the cities,

because in each one the greatest and most powerful of the citizens act as Rome's

guardians. . .. The masses are protected from the powerful ones by the authority

of Rome, so that rich and poor are equally contented and equally benefited.'

This amicable concord was part of the system that Roman rule had built up in the

provinces. The wealth became concent trated in the hands of a few leading

families. These were Rome's friends; they acquired Roman citizenship and, like

Aristides himself, two Latin names; and local government was firmly placed in

their hands. They did not always exert their

introduced about the time of his birth by the emperor Hadrian, he settled at

Smyrna and with the help of a strong constitution devoted himself to the care of

his health. He nevertheless found leisure for rhetorical exercises, and the

address that he delivered to the Romans about ad 143 strikes the keynote of the

'Golden Age': 'As though on holiday,' he tells the Romans, 'the world has shed

its burden of arms and devotes itself freely to beautification and festivity of

every kind. The cities have relinquished their old feuds; and a single rivalry

possesses every one of them -to be the best and most beautiful of all.

Everywhere are gymnasia, fountains, arches, temples, town halls and schools. The

ailing world has been, so to speak, scientifically restored to complete health.

Donations flow perpetually from you to the cities; and no one can tell who gets

the largest share because your bounty is so impartial. The cities positively

gleam with radiance and charm, and the whole earth is a pleasure garden. The

smoke of burning homes and warning beacons is gone with the wind from the face

of land and sea; instead we are confronted with spectacles of manifold charm and

an infinitude of public games. Thus, unquenchable like a sacred flame, the fair

never stops but passes on from place to place; and it is always continuing

somewhere, for the whole world has quahv fied for these blessings.'

They had never had it so good. 'There is no need of garrisons in the cities,

because in each one the greatest and most powerful of the citizens act as Rome's

guardians. . .. The masses are protected from the powerful ones by the authority

of Rome, so that rich and poor are equally contented and equally benefited.'

This amicable concord was part of the system that Roman rule had built up in the

provinces. The wealth became concent trated in the hands of a few leading

families. These were Rome's friends; they acquired Roman citizenship and, like

Aristides himself, two Latin names; and local government was firmly placed in

their hands. They did not always exert their powers for the benefit of the whole

community. Those who wielded power in the cities must often have been torn

between two conflicting ambitions - to use the public funds to make their cities

more impressive, or to enlarge their own private fortunes. We occasionally read

of popular indignation against magnates who contributed too little for

improvements or entertainments in their cities; and though public works and

spectacles were not the only legitimate objects of expenditure, the surviving

remains and inscriptions of the cities are often a good index of the social

conscience that prevailed.

In Bithynia and Pontus very little trace survives of the famous cities - even of

Nicomedia and Nicaea which kept up a bitter rivalry for precedence in the

province. As against this, we have an authoritative record of conditions there

in the correspondence of Pliny the Younger, who was sent out by Trajan in the

year in as a special commissioner to correct abuses. Before Pliny's arrival,

public works had been sanctioned on a considerable scale in several cities and

the money had been paid out from the city treasuries; but there was surprisingly

little to show for it all. Nicomedia had spent the equivalent of some tens of

thousands of gold pounds on two successive schemes for an aqueduct, and both had

been abandoned. At Nicaea the substructures laid for a theatre were condemned as

unsound after £100,000 had been spent on them. Leading citizens were owing large

sums to the treasuries, and they had been refusing to pay the fees due from

them. There was a reluctance in some places to submit accounts for scrutiny; and

from Pliny's ingenuous statement the experienced emperor had no difficulty in

surmising that money paid out for public works had been going into private

pockets. We have also an interesting sidelight on imperial policy in the

correspondence. A fire had raged unchecked in Nicomedia and destroyed many

buildings, and Pliny recommended that a fire brigade should be formed. But

Trajan forbade this on grounds of public policy; for he feared that - as

happened in American towns of the nineteenth century

- the fire brigades would develop into well-organised political clubs. On the

other hand the practical emperor, who was so much concerned with waterways, was

gready interested by the Nicomedians' project of cutting a canal to connect

their lake by locks with the sea.

In Bithynia we see the evil effects of the Roman system. By way of contrast, the

public buildings and civic munificence of the cities of the south coast of Asia

Minor cannot fail to excite our admiration. The cities there had handsome

shopping avenues flanked by broad side/walks under the shelter of colonnades.

They had grand theatres and vaulted stadiums, ornamental gateways, and

monumental buildings inside the wall circuit. Here, as in the leading cities of

Ionia, Aelius Aristides' sermon is not belied; and granting that the southern

cities have been fortunate in the chances of survival, it seems nevertheless

true that the very ruins of a place like Pamphylian Perge amount to more than

the magnates of Nicaea ever erected. At the neighbouring site of Aspendus, which

was never a city of much consequence, a theatre over 300 feet across was built

out at the foot of the citadel hill in the second century after Christ; made of

local stone by a local architect, it has successfully withstood time and the

elements; and only the loss of the marble facing of the stage background mars

the clean lines of the original construction.

Haifa mile away, the ruined aqueduct, with its single tier of arches, still

courses for many hundreds of yards across the plain. As it approached the

citadel, the water was piped up to a tank raised on arches 100 feet above ground

level, and from there it was carried by normal flow into the town.

Cyprus and Phoenicia flourished under Roman rule. Egypt, won from the Ptolemies,

was the emperor's special domain. Never at rest, Judaea blew up in the time of

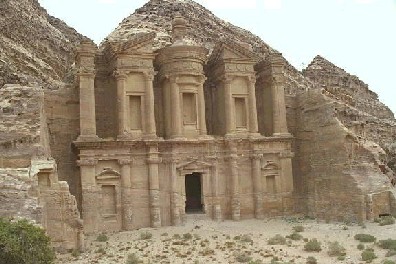

Hadrian. South of the Dead Sea, in the region of the rift valley that extends to

the Gulf of Akaba, the wilderness had once been awakened to agricultural and

industrial life by Solomon. After the time of Alexander the Great it was brought

to life again by the Nabataean Arabs, who commanded the caravan routes centring

on Petra and by their works of water conservancy made the desert habitable.

Allied to Rome, they were only brought inside the Empire in ad 106.

Coele Syria between the Orontes and Jordan valleys belonged to the Ituraean

Arabs and had relatively little urban development. But in Roman times a colony

was formed at Ba'albek, whose Greek name was Heliopolis (City of the Sun); and

here on the watershed between Lebanon and Antilebanon a huge sanctuary was

built. In terms of sheer acreage, weight of stone, dimensions of individual

blocks, and the amount of carving, this precinct can scarcely have had a rival

in the GraecoRoman world.

The sacred enclosure of Ba'albek measured about 300 yards in length, the whole

forming a great platform. At the east end stood a propylaea between two towers,

approached by a stairs-way 150 feet broad. Inside this was a hexagonal forecourt

giving access to the main temple court. The latter was surrounded by a

colonnade, behind which the wall was diversified by alternating semicircular and

oblong bays fronted by columns. The west side of this court was closed by the

great temple of Baal, which was 100 yards long and stood on a podium 45 feet

high. A row of half a dozen columns 65 feet high still stands in position, and

the entablature over them is elaborately carved; but so little else remains of

this gigantic structure that the visitor is left wondering whether it was ever

more than a fragment. Alongside this podium a smaller temple was erected at a

lower level; and this second building, itself no smaller than the Parthenon, is

still standing almost intact. Its spacious interior is articulated by engaged

Corinthian columns; they carry a complete entablature on which the ceiling

rested, and between them were arched and gabled niches which will have enshrined

statues of deities. Finally, outside the precinct stood a little temple which

consisted of a circular cella entered through a normal porch. This little

building shows some architectural subtlety; the outer columns of the rotunda

carried a lunate entablature which helped to take the thrust of the dome; and

the capitals, cut with five sides to conform to the unusual design, reproduce on

a smaller scale the arcs of the entablature above.

The architects employed at Ba'albek were no doubt skilled in their profession;

indeed, the neighbouring city of Damascus produced the most famous architect of

Trajan's reign. The workmanship at Ba'albek was equal to the best of its time;

and the architectural facades will have been enlivened by innumerable statues in

the niches. Yet the sheer opulence and endless repetition of the same motifs of

imperial baroque induce in the spectator a feeling of satiety. The Roman world

was incomparable in its engineering; but in its artistic sensibility, as in its

taste for food and literature, it had a unique immunity from any feeling of

indigestion. Magnificence was an end in itself, irrespective of what might lie

behind; and it is characteristic of Roman imperial architecture that the same

grandiose facade, with its ornate composite or Corinthian order and two/storeyed

bays and niches, could with scarcely any modification serve for a gateway, a

theatre scene, a city fountain, a public library, or simply as a screen to

exclude the outer world.